‘62 people are as wealthy as half the world.’

I haven’t been blogging lately because I took on two small writing jobs, and, like most writing jobs – big or small – they took longer than anticipated. Plus I was visiting my beautiful nieces and their progeny and returned late last week. But now the writing jobs are (nearly) finished and I’m back here.

Finally we got a new fridge at our house. The previous one was an old biological specimen fridge that we got for free from a university biology/zoology department (Bozo at ANU) nearly ten years ago. Like most people I put stickers, postcards, photos and bits and pieces on the fridge, which I delete from and add to from time to time. When the new one came I took them off and culled them all for a fresh aesthetic start.

One of the bits of paper held up by my wooden pear magnets was an article from The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 Jan. 2016. The headline says:

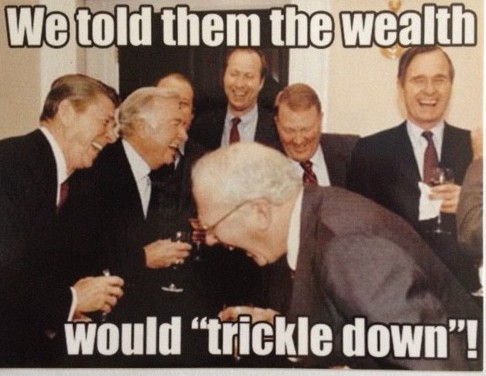

‘62 people are as wealthy as half the world.’

If there are about seven billion people in the world this means that 62 people are as wealthy as three and a half billion people. It’s hard to comprehend. I can sense that a billion must be really, really big because I know that on our overcrowded planet with about 350,000 babies born per day, there are still only 7 billion of us. But I can’t really comprehend how many a billion is, or I couldn’t until I read the following.

John Lanchester in his wonderfully clear, easy-to-read book Whoops! Why everyone owes everyone and no one can pay (Allen Lane, 2010) has a way to get some sense of how much a billion is. He quotes it from Alan Paulos’ Innumeracy (1990), which I haven’t read, but with a title like that, I should. Here it is.

‘Without doing the calculation, guess how long a million seconds is. Now, try to guess the same for a billion seconds. Ready? A million seconds is less than twelve days; a billion is almost 32 years.’ (Lanchester, 2010, p. 2)

The Australian politician and writer Andrew Leigh (The Canberra Times, July 2015) quoted another easy way of conceptualising something, in this case, wealth. Imagine wealth as the height of a person. So let’s take a slice of Sydney. Some people are actually under the ground by a very long way – they’re in debt. Others have their heads just above the ground. And some are so wealthy that they are as high as Sydney’s Centrepoint Tower (which is about 305 metres, more than twice as tall as Sydney Harbour Bridge).

How and why such inequality came about is explained clearly in Lanchester’s Whoops! Why everyone owes everyone and no one can pay (Allen Lane, 2010). He also writes:

‘The language of money is a powerful tool, and it is also a tool of power. Incomprehension is a form of consent. If we allow ourselves not to understand this language, we are signing off on the way the world works today—in particular, we are signing off on the prospect of an ever-widening gap between the rich and everyone else, a world in which everything about your life is determined by the accident of who your parents are.’ John Lanchester in The New Yorker 14 August 2014.

We live in a world brimming with unfairness and pain. But it’s important to be aware of why, yet also to be aware of the beauty and grace in life. We have to focus on the beauty and grace or we’d go mad. Luckily, many of the latter are free, like love and libraries and blogging!

(P.S. Assuming basic needs, such as a roof over our heads and enough food, are met, and I know that is a big assumption in a world as unequal as ours. But I’m communicating with an audience of whom I probably can assume those things – and are as angry as I am over the grotesque inequality and suffering of people less fortunate than we are caused by the greed of billionaires.)

[contact-form][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]

Leave a Reply