‘Set wide the window. Let me drink the day.’ American writer Edith Wharton (1862-1937) wrote that. I love it and would often think of it after opening the curtains first thing.

‘Set wide the window. Let me drink the day.’ American writer Edith Wharton (1862-1937) wrote that. I love it and would often think of it after opening the curtains first thing.

But her words took on a tragic tone in the mornings after the bushfires began. We could no longer open windows. Canberra’s air quality suddenly became literally the worst city in the world.

Actually it wasn’t as sudden as it seemed. Canberra’s air quality has been gradually worsening in the past few years, along with the rest of the country’s, thanks to our Government doing less than nothing about vehicle and other emissions responsible for raising CO2 levels.[1]

But I was aiming at an uplifting, positive post, damn it! I normally slant towards the upbeat, the whacky, the whimsical, but before veering in that direction, a serious point needs to be acknowledged.

Melancholy

The ramifications of the bushfires for our mental health are important as well as those for our physical health but less attention is paid to this. In the words of a former counsellor I am ‘emotionally robust’ but even I’ve had to struggle with melancholy in the past month or so. I’ve had to rearrange my psyche to regain my hard-won emotional equilibrium.

Because of successful counselling in the distant past, I’ll never get depression again. (Sad, bereaved, unhappy sometimes – very probably, almost inevitably, but not depressed.) It took about two years from 1985 to 1987: six months to cope with chaotic events and eighteen to reflect on and analyse what they meant. If I hadn’t achieved that, I’d be depressed now, especially with Australia’s political situation and both main parties’ irresponsible stance. As it is, all I get is melancholy. To get out of the melancholy, I dance tango, swim, do yoga and meditation, and absorb books, films and art. Not to mention writing and some wonderful friends.

Focusing on the positive

To focus on the positive is an art in itself, and, life being what it is, an essential one, and if it could be judged academically, I’d have a PhD in it.

My real PhD covers history and fiction. I started off with the history in fiction. It was but a short step to realise the necessity of exploring the fiction in history.

I was being paid to research and write. (PhD scholarships are famously minimal but time is more important than money, and in any case, I’m very cheap to run.)

I spent part of this luxurious time steeping myself in the biographies of artists. My favourite was surrealist painter Dorothea Tanning’s, Between Worlds (2001). Her work is amazing and she was married to my other favourite surrealist, Max Ernst. She also lived to an amazing age (1910-2012). In later life she began to write poetry, joking about being ‘the oldest living emerging poet’. Up to the end she was getting her poetry published in the New Yorker.

Creative Lives

During the PhD I also read biographies of people whose papers I was working on for the book, Creative Lives (NLA, 2009). One of these was Australian novelist Christina Stead (1902-1983). She maintained that she would not write her autobiography because so much of her life was in her fiction. (While it may be true, this stance understates the talent and intellectual dexterity necessary to transform life into art, as Anne Pender argues in her lucid, beautifully written biography, Christina Stead: Satirist [Common Ground, 2002].)

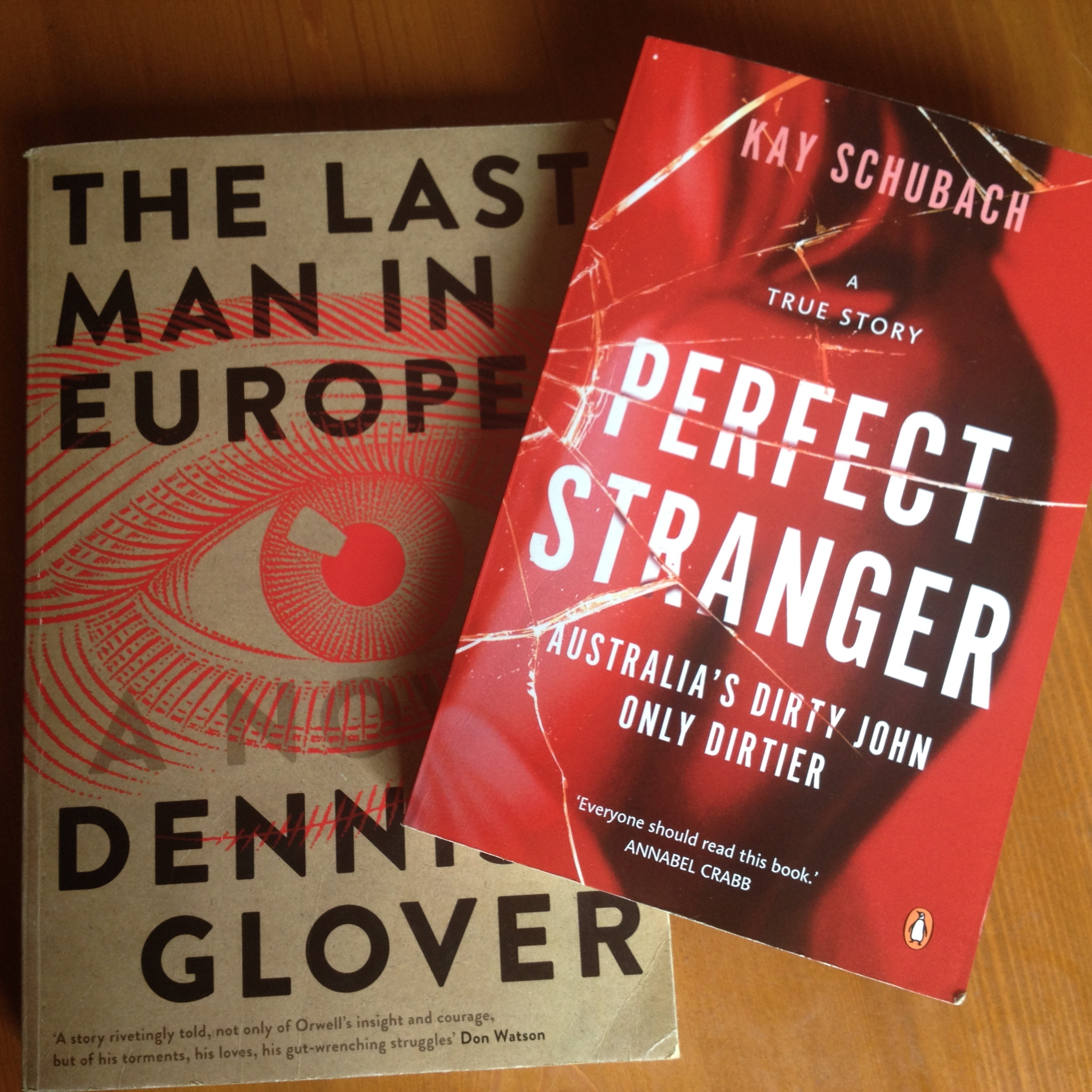

My favourite recent biography is in the form of a novel, based on the last few years of George Orwell as he struggles to conceive and write Nineteen Eighty-Four. Evocative and absorbing, it transports the reader into that life. It’s Dennis Glover’s The Last Man in Europe (Black Inc., 2017). The relevance of both books to current events we’re living in now can hardly be overstated, as many realised soon after the election of Donald Trump when Nineteen Eighty-Four suddenly rose to Number One in the Amazon best-seller list. Almost overnight there was an increase in sales by 9,500 per cent. See here

Brave biographies

I picked up the following book at the Potts Point Bookshop the other day. Australian high flyer Kay Schubach wrote Perfect Stranger (Penguin, 2012), to relate how, at a vulnerable time in her life, she fell precipitously in love with a charismatic, handsome man who, once they became lovers, turned into an obsessively jealous, violent control freak. It’s lucidly written and riveting. I cannot put it down.

Also, it shares something admirable with two favourite biographies I’ve mentioned before in a 2016 blog – Jonathan Self’s Self Abuse (John Murray, 2001) and David Leser’s To Begin To Know (Allen & Unwin, 2014). All three biographies demonstrate the courage of their authors in the painful honesty of what they’re willing to reveal to readers about themselves. That takes guts.

Biography used to be not taken seriously in academic circles. Thankfully, brilliant writers like Richard Holmes (b. 1945) helped to change this. His many powerful, innovative biographies include The Age of Wonder, which investigates the Romantic generation’s discovery of science, covering the 1760s to 1833, when the word ‘scientist’ was coined.

What will our age be called? The Age of Plastic? The Age of Idiocy? The Age of Lies? Or The Age of Greed?

People in the future, if any survive, will see that Greta Thunberg was our Cassandra.

Emotional equilibrium

I wanted to end this post on an upbeat note – clearly it is better to laugh than to cry, and in many circumstances the choice is ours. I’m reminded of something that the Italian film director Federico Fellini once said: ‘The pearl is the oyster’s autobiography.’

Humour obviously promotes emotional equilibrium and another thing I could have added to my coping list above is Netflix’s Derry Girls, Lisa McGee’s coming of age comedy, set in the 1990s against the background of The Troubles.

The series could be seen as a memoir. Lisa McGee said that depictions of The Troubles in Northern Ireland were ‘grey and masculine … and humourless.’ Later, when she started to write Derry Girls she said that she drew on how, in those uncertain times, perhaps in order to cope, ‘we developed this weird sense of humour about it.’ (LA Times, 15 August 2019, read the interview here)

Derry Girls is hilarious, and an interesting thing about it to someone who went to Catholic convent schools in Australia is the lack of change in them, even in another country, from the 1960s to ’90s. Everything the same as in the 1960s except for more swearing and fewer nuns.

[1] The Guardian Weekly, 15 Nov 2019, ‘Emission impossible: why are cars still so dirty?’ by Royce Kurmelovs

Leave a Reply