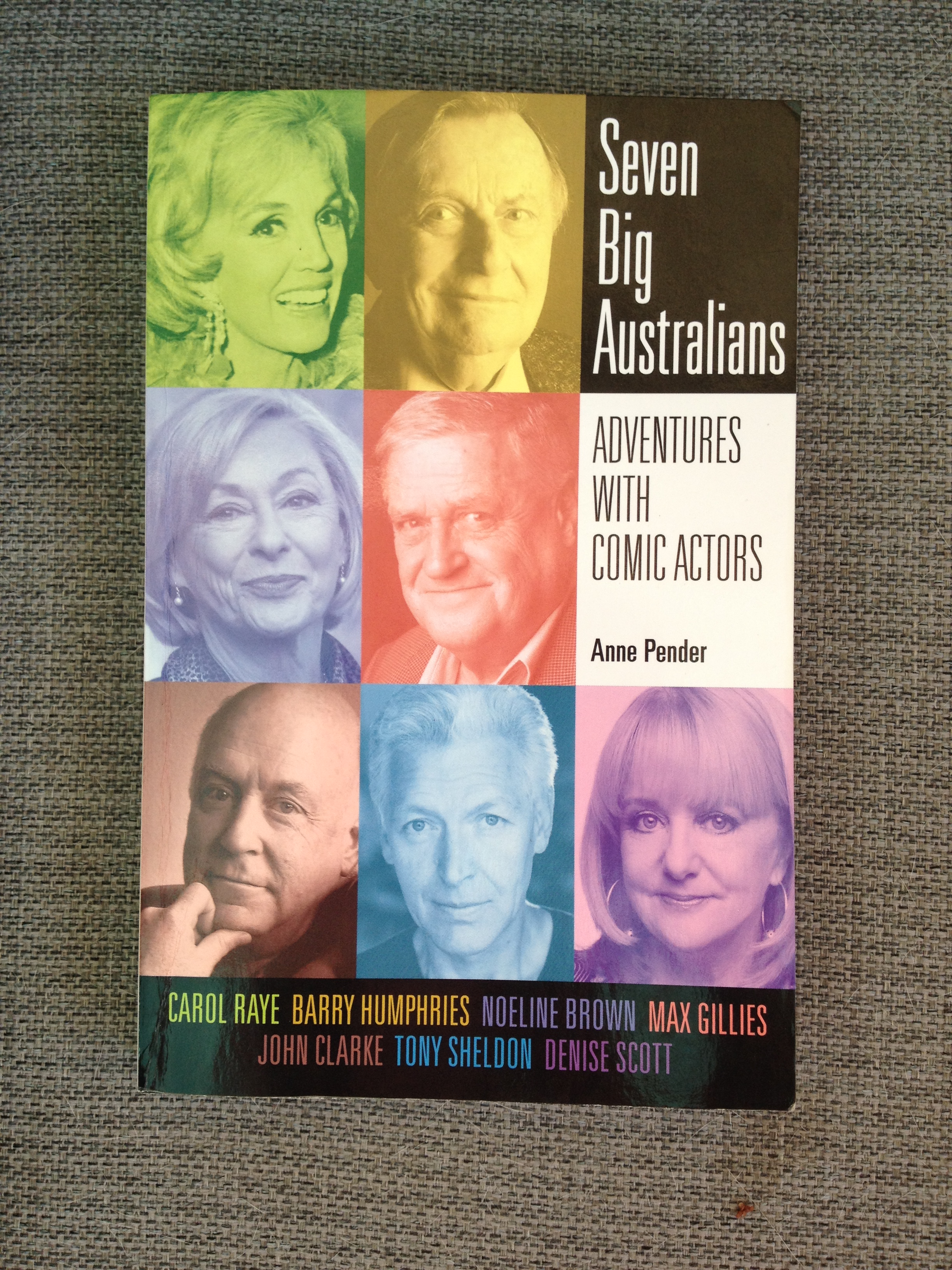

In Seven Big Australians: Adventures with comic actors (Monash University Press, 2019) Anne Pender paints an unforgettable portrait of the lives of Australian comic actors: Carol Raye, Barry Humphries, Noeline Brown, Max Gillies, John Clarke, Tony Sheldon and Denise Scott. She brings to life careers that span from the Second World War to the present.

These portraits are also a portrait of the times, giving insights into Australian society just after the Second World War and of the tremendous social change in Australia from then until now.

Because the author interviewed her subjects over a five-year period, and knew some for much longer, the reader feels an intimate connection with them. We hear about their disappointments and triumphs, their failures and perseverance in their own heart-felt words.

These performers pioneered new forms of entertainment, bringing the vernacular centre-stage and transforming traditional comic genres. We see fascinating behind-the-scenes details about groundbreaking shows like The Mavis Bramston Show, The Gillies Report, Clarke and Dawe and The Games. One of the many treasures in this book is seeing these actors demonstrate their versatility and resilience, some of them rising to challenges that involve reinventing themselves and their careers in response to changing times.

Show business and satire

The talented and prolific Carol Raye produced and starred in the ground-breaking satire, The Mavis Bramston Show, and also contributed to innovative theatre on stage and on television for over four decades.

Noeline Brown, with her golden good looks and low, sexy voice, was also in The Mavis Bramston Show. She worked on stage, on television, cinema and radio, e.g., The Naked Vicar Show, which presented parodies of television, especially pompous British documentaries that filled Australian programs of the time.

Tony Sheldon had high profile show-business parents, Frank Sheldon and Toni Lamond, and his childhood was punctuated with the drama and tragedy of the consequences of their volatile relationship. Sheldon grew up to play roles in such productions as A Hard God, Torch Song Trilogy and the lead in the musical stage adaptation of Priscilla Queen of the Desert, here, in London’s West End and in New York.

Over more than three decades Denise Scott has acted in a comedy troupe, in stand-up comedy, on radio and television, and more recently as an actor in several television series. Her ‘stridently Australian’ comic style demonstrates courage as she persisted, managing to break through the many barriers for women in comedy.

Scott suffered years of crippling stage fright. As Pender reveals Scott’s real-life excruciating failures in front of hostile, heckling audiences, we want to cringe and blush, and can only admire the guts Scott showed in persevering through the hard times.

Now her interactions with audiences is her strength, one of the funniest elements of her act. She won the Helpmann Award for her show Regrets. She performs regularly on television and in shows such as Disappointments with Judith Lucy to packed theatres all over Australia.

Intriguing psychological insights

Pender wrote a biography of Barry Humphries, One Man Show: The stages of Barry Humphries (ABC Books, 2010), and as in that book the author does so much more than write about the life and career trajectory of each performer; she shares intriguing psychological insight and puts the performer into a wider context.

We see the rigidly conformist Australian society of the 1950s in Barry Humphries’ youth. At Melbourne Grammar he hated sport and refused to cooperate, preferring to escape to a second hand bookshop. Caught and punished, he developed a way to survive by provocation.

‘When he was called to the headmaster’s office and reprimanded for failing to cut his hair to regulation length, he stared coolly and said, “There’s one man in the chapel that has hair that is longer than mine. His name is Jesus.”’

Seeing comparisons and contrasts in the wide variety of Australian comic actors, the reader gains a vital sense of the wider landscape of Australian humour. Max Gillies wasn’t the only one who ‘had a knack for mockery of the larrikin foibles of Australian men, and their awkward performances of masculinity. Barry Humphries and Paul Hogan parodied men in their own comic creations. Max mimicked real, high profile men and his parodies were unique in their sharpness and vigour.’ (p. 133)

In The Gillies Report, Gillies played politicians such as Fraser, Hawke, Whitlam, Gorbachev and Thatcher. ‘The writing was clever, politically astute and attuned to the theatre of politics and the strutting star turns of our elected leaders.’ (p. 178)

A distinctive forms of comedy and a rich legacy

John Clarke, who played a newsreader in that show, wrote all his own news bulletins just before the program. Some sketches were light and whimsical and others dark, biting satire. He parodied the Australian obsession with sport, inventing a new sport called farnarkeling.

Clarke had writing or acting roles in many films. In the early 1980s Phillip Adams introduced him to filmmaker Paul Cox. Clarke and Cox collaborated on the script of the wonderful film, Lonely Hearts, which won Best Film at the AFI awards. Many remember his understated and hilarious performance with Sam Neill and Zoe Carides in the 1991 black comedy directed by John Ruane, Death in Brunswick.

The long-running series of mock interviews with politicians, Clarke and Dawe, began in 1989. It focused on the peculiarities of each politician, ‘revealing Clarke as a highly original performer who has perfected a distinctive form of sketch comedy.’ (p. 185)

When John Clarke co-wrote and acted in The Games he pioneered a new form of comic drama. He said:

‘The idea was to shoot a satirical drama that appears to be documentary so it looks real, only we’re monkeying with the visual grammar, we’re asking people to question the way they watch things; is it true because it looks true and if it isn’t, are the other things that look true actually or possibly false?’ (p. 183)

Pender captures something of the rich legacy left to us by John Clarke, commenting on the ‘discipline, skill and intense focus’ of his writing. She continues: ‘His satirical wit relied on comic judgement and restraint. Clarke’s writing, like his personality, was outward looking and generous, and his work is a gift both to the audience and to the larger democratic project in which satire plays a glorious and vital part.’ (p. 191)

Seven Big Australians is worth buying for the John Clark section alone. But all chapters are fascinating. This book, dense with a wealth of detail, rewards re-reading. And because of the author’s light touch and clarity, the writing is not dense. It’s insightful and funny, a joy to read.

Leave a Reply