Robert Dessaix seems like one of the last people in Australia to be qualified to write a book about leisure. He has written many books, he taught Russian at two universities, and he has been a radio presenter for long-running programs. A glance at his achievements gives the impression of an industrious and productive life, possibly one of unremitting toil.

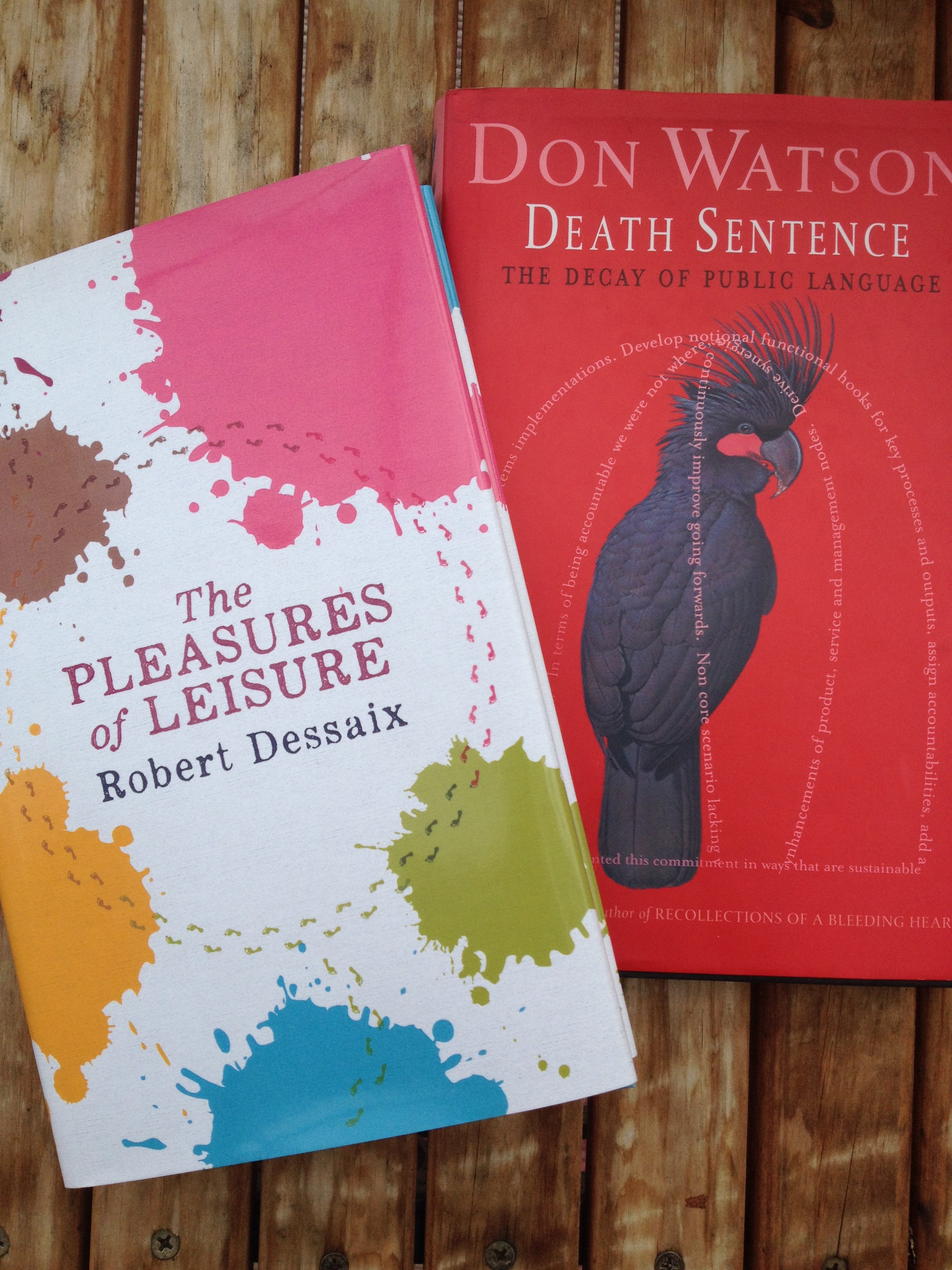

Recently I went to a lunch at Muse bookshop and restaurant www.muse.com.au with Robert Dessaix and a few other convivial, interesting people. We ate delectable food, drank good wine and listened to Robert Dessaix talk about the life of leisure and how he came to write a book about it. A copy of it, The Pleasures of Leisure (Knopf, 2017), was included in the very reasonable price of the lunch.

Dessaix admitted that leisure was something he ‘never quite got the hang of’, knowing only how to fill vacant time usefully and productively. In the book he tackles aspects of leisure such as loafing, reading, walking, nesting, travelling, taking siestas and meditating. With the notion of loafing in mind, he reflects on his childhood:

‘I’d never nonchalantly arrived at anything at all (although from an early age, by dint of hard work, I could say “nonchalant” in several languages’ (p. 5).

Why do words go out of fashion?

Loafing is not a word you hear much these days. It produced in me connotations of disapproval, probably from my mother’s attitude, and loafing was definitely one of her words. The opposite of loafing, in her vocabulary and moral universe, would have been expressed by ‘gumption’, another word we don’t hear much these days. (Why is that?)

Let’s break out of that set of brackets, or parentheses, and ask why do words suddenly go out of fashion? For example, almost no one says ‘probably’ any more – they all say ‘likely’ – our usage of that word has gone the American way. We used to only use it as an adjective; now we use it as an adverb. Probably people started feeling that ‘probably’ sounded too vague, and ‘likely’ sounded more precise plus had a more positive tone about it. But I am digressing widely off the mark here and taking a stroll down the word use area and away from Robert Dessaix’s use of words.

Socrates couldn’t think of anything more boring

At the lunch Dessaix talked about walking – or rather sauntering and strolling. Walks, he pointed out, don’t have to be limited to the bush; we can stroll through streets and malls; we can saunter wherever we happen to be.

‘The important thing,’ he said, ‘is that you must be unplugged!’ Don’t take the iPad or the iPhone. It is an opportunity to simply be where you are, existing in the present moment. And you can stroll through shops; just don’t actually shop. ‘Flirt with the world,’ he said, ‘You don’t have to own it or buy it.’

Walking can give us the feeling of doing something and nothing at the same time. We know the ancient Greeks walked for its own sake, idly sauntering through the woods, because Socrates is on the record as saying that he couldn’t think of anything more boring.

It’s different for us, of course, because walking is not our main means of transport. Walking is a novelty, different from going by car, train or even bicycle. When I cycle, I notice all the trees, as opposed to whizzing past, not registering them, in a car. But when I walk, I notice every leaf on every tree.

I’d like to be idle but intellectually occupied. I’m rarely idle but I am lazy. I dislike physical work but I know how good physical exercise makes the body and spirit feel. If I find time on my hands, which is almost never, I read. What else do I do with my time? Work, which is writing, which involves researching, which involves more reading.

Here endeth the lesson

Robert Dessaix’s conversation was a delight – entertaining and amusing – and his new book has the same flavour, being erudite but light-hearted, and warmly human. These days, many people not only write ugly corporatised language with nothing human in it – they talk like that too! I was at a book launch a while back and an aquaintance from my old ANU days started chatting. She started talking in this corporatized managerial-speak and I was so shocked that my jaw dropped open and I started backing away in horror, claiming I desperately needed another drink. Some people are so alienated from their mother tongue that they don’t know what’s coming out of their mouths.

Such language, which countless people are forced to speak, read and hear every day of their working lives, is ‘depleted and impenetrable sludge’ (Don Watkins. Death Sentence: The decay of public language. Knopf, 2003, p. 24).

When people talk honestly about what they think and feel, their speech won’t be peppered (I should say blandified) with ‘empowering the stakeholders’ and ‘key performance indicators’ and ‘implementing strategies for key deliverables going forward’. They won’t tell you about being ‘negatively impacted’ and they sure as hell won’t put an ‘s’ on the present participle ‘learning’ and think that it is the noun form of that verb. What they have forgotten is what every two-year-old English speaker knows: the noun form of the verb to learn is ‘lesson’.

And here endeth it.

(Readers younger than I am probably won’t know that ‘Here endeth the lesson’ is from the King James Bible and was a traditional closing sentence after an Anglican sermon. It also comes in handy for a bit of irony and self-mockery.)

Leave a Reply